Buoy Conversion Kit for Teledyne RDI Pinnacle ADCP

Announcement

In a joint product release with Teledyne RDI, DeepWater Buoyancy announced a new product – the Buoy Conversion Kit for Teledyne RDI Pinnacle ADCP.

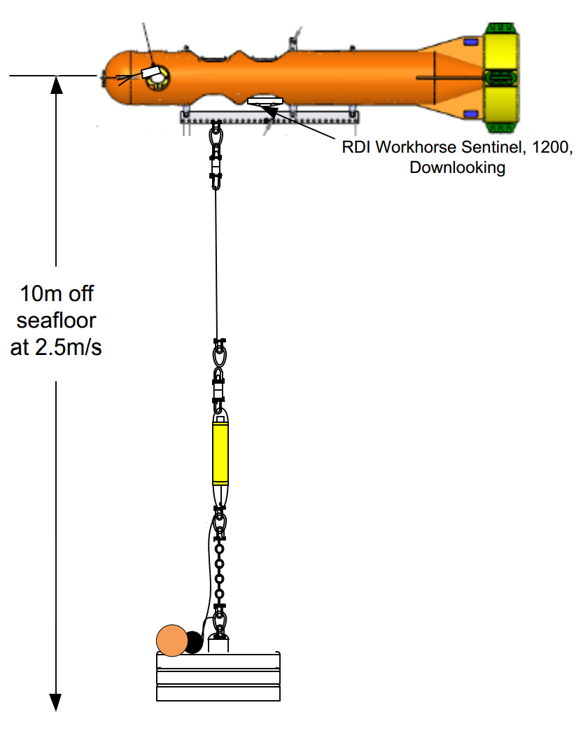

This kit allows the use of Teledyne RDI’s new Pinnacle ADCP on existing DeepWater Buoyancy ADCP buoys.

Designed in collaboration with Teledyne Marine’s Product Development Team, the kit includes an ADCP clamp, top frame, and lift strap system.

About the ADCP Buoy Conversion Kit

DeepWater Buoyancy collaborated with the Teledyne RDI product development team throughout the design of the Pinnacle ADCP. Features were incorporated into the Pinnacle housing to allow for secure mounting of the instrument in DeepWater Buoyancy ADCP buoys. Darryl Symonds, Director of Marine Measurements Product Lines for Teledyne RD Instruments said, “We have been working with the DeepWater Buoyancy team (formerly Flotation Technologies) for decades. This latest collaboration on the Pinnacle product is just the most recent in a long history of successful co-design that started with the very first subsea spherical ADCP buoy in 1986.”

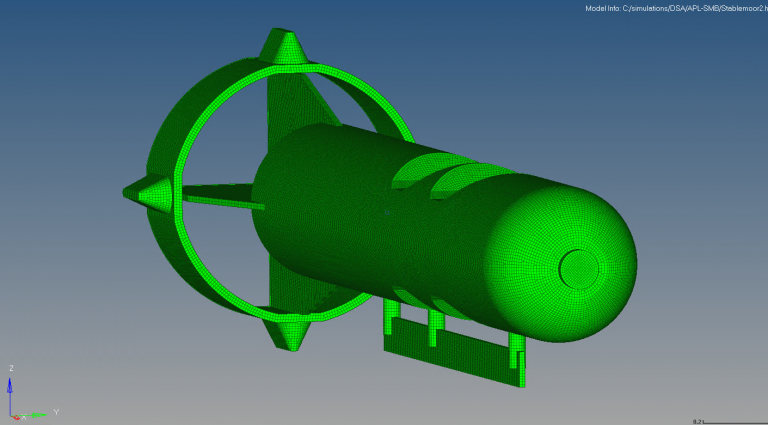

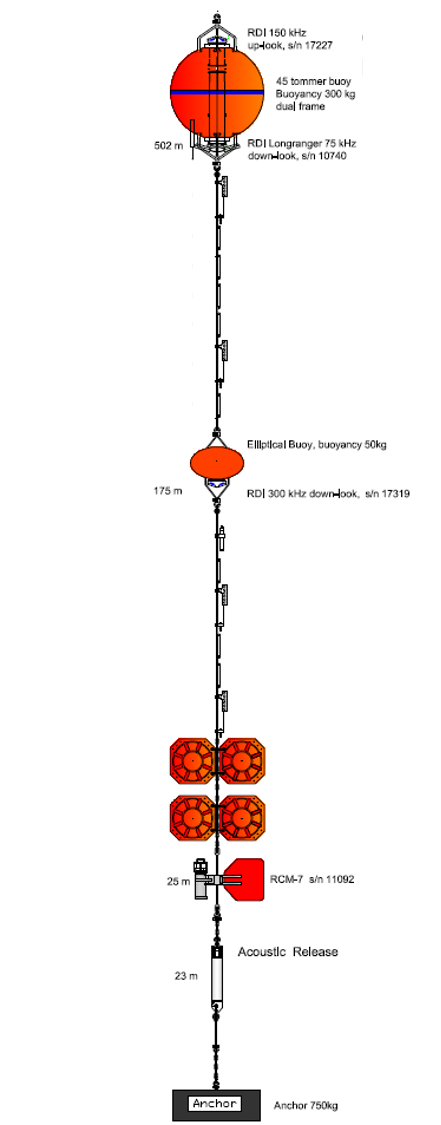

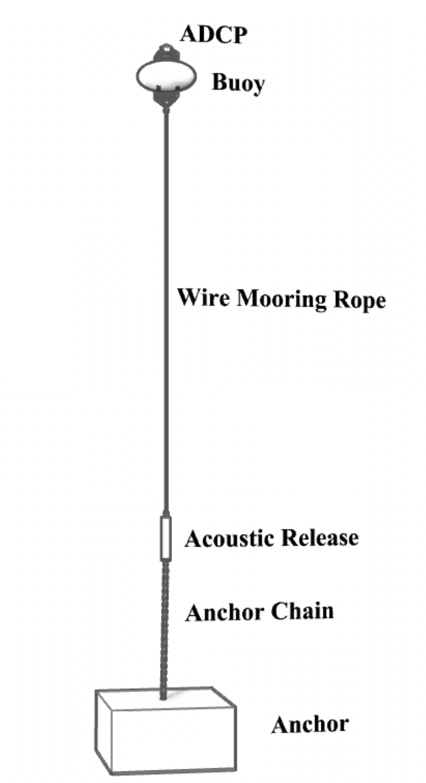

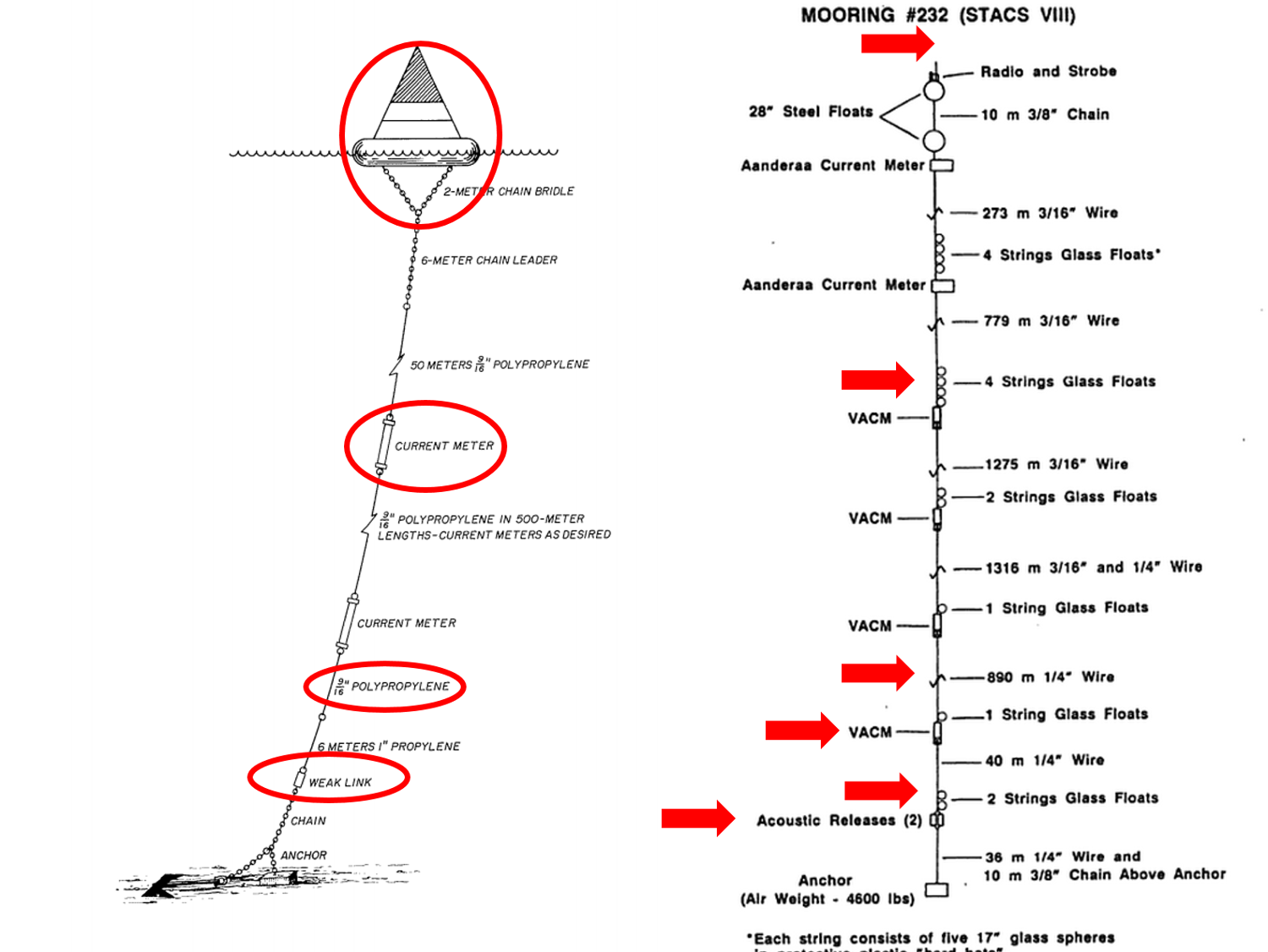

The kit consists of three assemblies: the clamp, the frame and the buoy lifting straps.

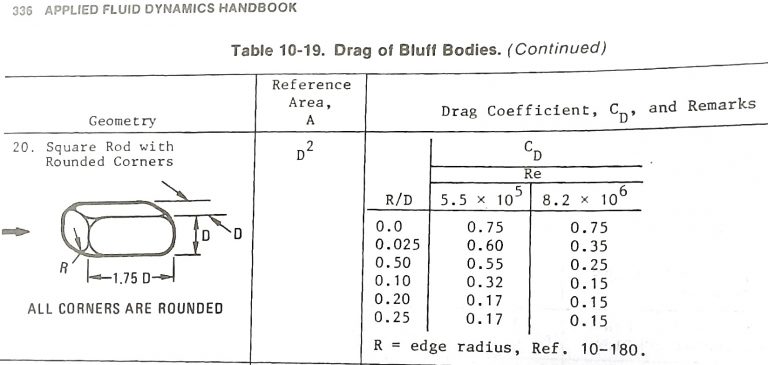

The Clamp

The clamp is similar to the standard ADCP clamp in that it is made of urethane and fastened with titanium hardware for superior corrosion resistance. It is unique, however, in that it has a “keying” feature that ensures that the Pinnacle is “clocked” correctly. Unlike a standard ADCP, the Pinnacle has no obvious “lobes” to ensure that the beams pass between the top frame legs. Instead, it has a flat face. So the joint engineering team placed a key on the Pinnacle housing to match a feature on the clamp to ensure beam location.

In addition to this key, there is a slot in the Pinnacle housing that matches a rim in the clamp. This ensures that there is no axial movement of the instrument during handling and deployment.

The clamp has composite loops that allow a fiber lifting strap to be passed through. These straps allow for safer and easier handling and mounting of the ADCP into the buoy.

The Top Frame

The conversion kit frame is noticeably longer than a standard ADCP frame. This is to provide the appropriate space above the transducer face for the acoustic beams to develop. Additionally, the frame has a feature to allow the connection of the Buoy Lifting Strap for safe handling.

Like all DeepWater Buoyancy ADCP frames, it is manufactured with 316L stainless steel. It is then electropolished and fitted with replaceable zinc anodes for superior corrosion resistance. The frame arbor is fitted with isolation bushings and allow connection to the mooring line with standard shackles.

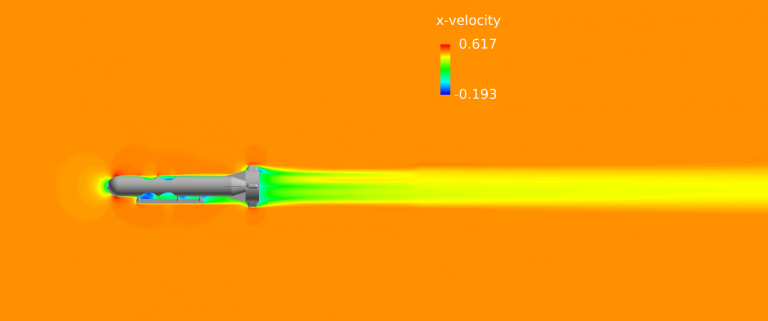

The Buoy Lift Strap System

Also included in the conversion kit is a Buoy Lift Strap System. Designed with Ocean Engineer Jon Wood of Ocean Data Technologies, the strap system allows for safe deployment and retrieval of the buoy. The strap allows the buoy to be lifted without placing unnecessary stress on the extended frame members and for the buoy to be lifted with its axis horizontal. In addition to the safeguarding of frame and instrument, the horizontal lift allows for a shorter lift height to minimize the A-frame and hoist specifications necessary for deployment and recovery. Jon Wood also points out, “In addition to being a tool for deployment and recovery, the strap system appears to act as a vane and reduces spinning motion of the buoy.”

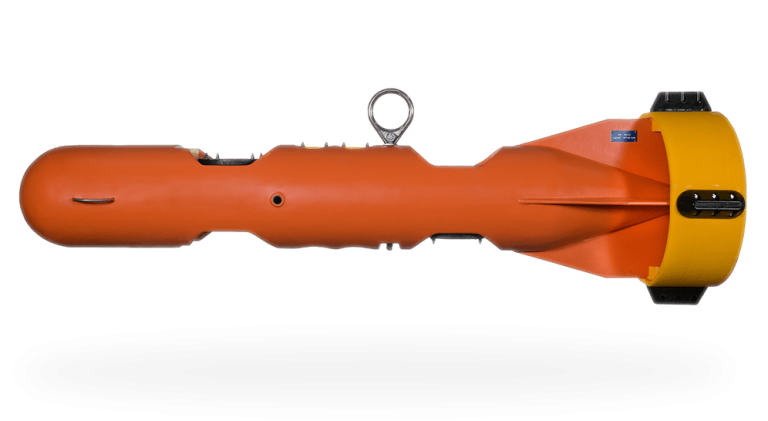

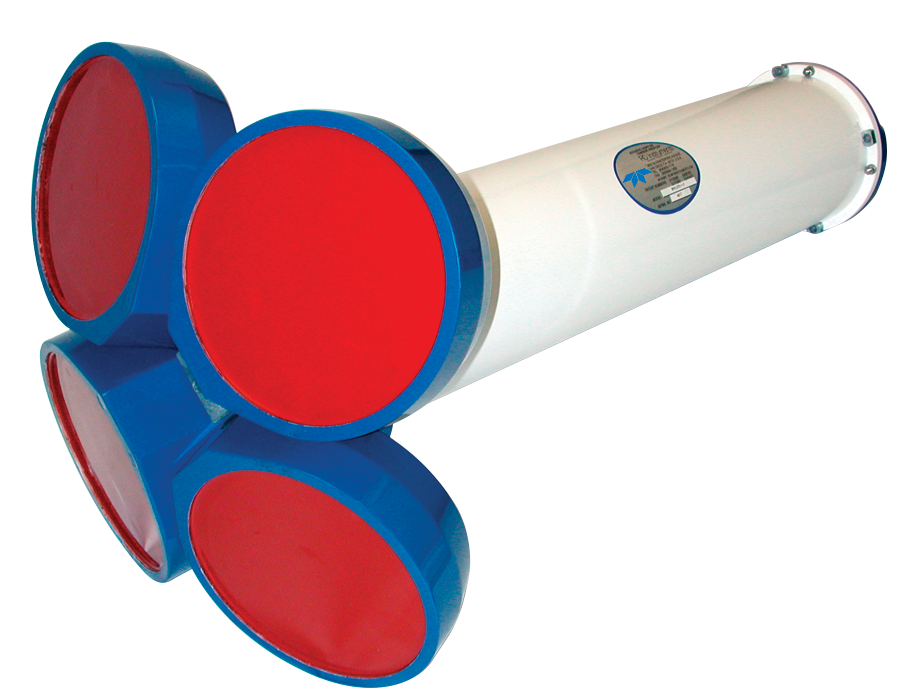

About the Pinnacle

Once again, Teledyne RD Instruments takes its rightful place as the leader in deep-water current profiling technology. Building upon the tremendous 20-year success of their industry-standard Long Ranger ADCP, Teledyne RDI is pleased to introduce their next-generation long-range ADCP—the Pinnacle 45.

Rated to a depth of 2000 m, the 45 kHz phased array Pinnacle ADCP delivers a 1000 m current profiling range with a decreased size and weight, a game-changing field-swappable configuration, and a long list of impressive new features and product enhancements, including:

- Swappable Configuration: Convert from Self-Contained to Real-Time without an additional purchase

- Adaptable: Independent or Interlaced long range and high resolution modes allow users to optimize their system for unique deployment requirements, offering the best of both worlds in a single instrument.

- Continuous Sampling: Pinnacle’s 4 beams ping simultaneously (as opposed to individually), allowing for simultaneous sampling of a full profile.

- Easy Data Access: Redundant MicroSD memory cards for added data security.

- Compass Enhancements: Pinnacle includes both heading field calibration and magnetometer data, allowing you to utilize either or both and to turn your mooring faster.

- Deployment Status Indicator: External LED light ensures you know the system is operational when deployed.

- Advanced Monitoring: Health Monitoring and leak detection provide users with the peace of mind that their system is operating as intended.

- Increased Data: 20° phased-array beam allows you to measure within 6% of range to surface (air/sea or bottom), closing the gap on missed data.

- Rugged and Robust: Independent main electronics housing and battery compartment and a no metal in contact with the water designed housing and transducer limit the risk of damage from leaks.

- Long Life: Alkaline or lithium battery compatible, with 18-month deployment durations possible on 4 Li batteries.

Learn how you can reach your Pinnacle at: www.teledynemarine.com/Pinnacle

About DeepWater Buoyancy, Inc.

DeepWater Buoyancy creates subsea buoyancy products for leading companies in the oceanographic, seismic, survey, military and offshore oil & gas markets. Customers have relied on our products for over thirty-five years, from the ocean surface to depths exceeding six thousand meters.

Learn more at www.DeepWaterBuoyancy.com

About Teledyne RD Instruments

With well over 30,000 Doppler products delivered worldwide, Teledyne RD Instruments is the industry’s leading manufacturer of Acoustic Doppler Current Profilers (ADCPs) for current profiling and wave measurement applications; and Doppler Velocity Logs (DVLs) for precision underwater navigation applications. Teledyne RDI also supplies Citadel CTD sensors for a variety of oceanographic applications.

Learn more at www.teledynemarine.com/rdi/